Following the classification of media systems by Hallin and Mancini (2004), Portugal belongs to the “polarised pluralist model” which has as one of its main characteristics a relatively low level of professionalisation of journalists. This means a low degree of professional autonomy, some weakness in the definition and implementation of distinct professional and ethical norms, and a relative lack of public service orientation. These traits do apply to the Portuguese situation, although with nuances (Fidalgo, 2008b; Santos, 2010).

During most of the twentieth century, because there was no freedom of expression or association, journalists’ professional organisations had no autonomy at all. In such conditions, it was particularly difficult for them to implement their specific ethical values and professional norms, and this contributed to a “weak professional culture” (Correia & Baptista, 2007). Things changed quickly after 1974 when democracy prevailed. One of the first laws to be put into practice was a new press law. Journalists organised themselves in a now free and autonomous strong national union and were able to convince political powers to make laws on a large set of items considered very important to journalistic work. If the instruments of journalistic professionalisation had been absent before, they were now conquered by the professional group, although more because of pressure on the state rather than because of a dynamic autonomous process. However, dependence on a very centralised state which is typical of “pluralist polarised systems” continued in the country.

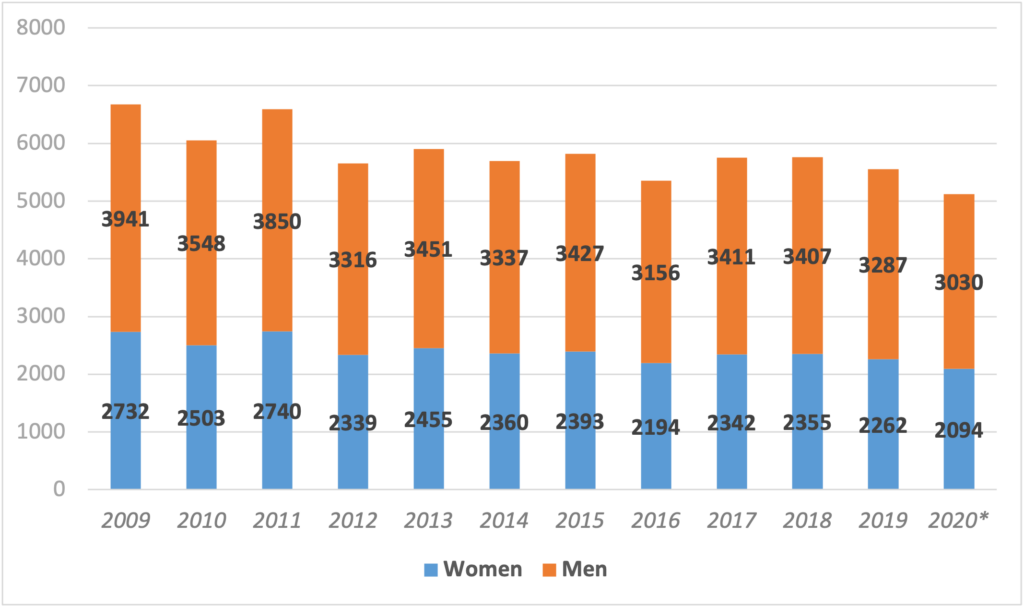

Portuguese journalists have important laws to protect their activity as well as their Code of Ethics but they were never able to put into practice an efficient and consensual mechanism of self-regulation. The existing Ethics Council works in the context of the union, but many of the 5,124 professional journalists that existed in May 2020[i] (see Figure 1) do not belong to it (according to the president of the Journalists Union, only about one-third of professional journalists are members) and, therefore, tend not to acknowledge its jurisdiction.

The teaching of journalism is very recent as well as it only appeared at a Portuguese university for the first time in 1979. But it then developed very fast and nowadays journalism courses (usually integrated into communication sciences courses), as well as Master degrees, are very popular in the country and are present in all relevant universities, both public and private. If we look at the group of actual professional journalists (5,124, of which there are 3,030 men and 2,094 women), it is relevant to notice that 43 per cent of them hold a university degree (bachelor, master, or PhD). This number goes up to 69 per cent if we include those who began a university course but never finished it. Female journalists with a university degree are 61 per cent (87% if we include university unfinished courses), while male journalists with a degree are 31 per cent (57% if we include university unfinished courses). This data confirms the idea that there are more young female journalists and more old male journalists who come from a time when no course was taken to become a journalist (CCPJ, 2020; Subtil & Silveirinha, 2017).

Journalists are a rather heterogeneous professional group and still have not succeeded in putting forward a strong collective dynamic. Some progress in recent years is partly counterbalanced by the negative economic situation in the media industry, which pushes journalists more towards proletarianisation than professionalisation. A 2016 survey among journalists (with 1,494 valid respondents) confirmed this increasingly difficult situation for the professional group: 80.6 per cent of them received less monthly pay than EUR 1,500 net and 57.3 per cent got less than EUR 1,000 per month and 11.6 per cent less than EUR 500.[i] The average monthly income for the respondents was EUR 1,113, which is, even for a poor country like Portugal, a very low pay. This is particularly worrying if we remember that most of the journalists have a university education and the work they do holds significant responsibility (Crespo et al., 2017). In this scenario, it is not surprising that 48.8 per cent of the journalists feel very unhappy with their labour conditions, and 64.2 per cent confess to having already considered leaving the job. In recent years many journalists decided to exchange journalism for another job in the area of communication such as public relations, press attaché, communication manager, marketer, and so on because they are usually much better paid, even though they have a lower status in terms of social recognition (Fidalgo, 2019).

[i] The number of journalists has decreased in recent years (see Figure 1), but it grew very quickly during the previous three decades: between 1987 and 2006, it increased from 1,281 to 7,402 professionals, most of them (ca. 60%) with some academic degree in journalism or communication sciences (Fernandes, 2008). It should also be noted that only 19.8 per cent of them were women in 1987, but the figure was about 41% of the total in 2006 – and this same percentage continues nowadays (41% women journalists, 59% men journalists) (Salim, 2008; CCPJ, 2020).

[i] Another survey of journalists, made in 2015 and involving 806 valid respondents, reached similar conclusions with 55.4 per cent of the inquired confessing to receiving less than EUR 1,000 per month (Miranda & Gama, 2019).