In Germany, about 52 per cent of those working in journalism and editorial boards were women in 2017, according to official jobs report (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2019b). These findings correspond with an International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF, 2011) study about female employees in important media companies in Western Europe. Taking a closer look at senior professional levels and higher, however, reveals the existence of a glass ceiling. In some media outlets, gender equality is accomplished at the lower levels of the professional hierarchy, but this is not true for leading positions in key media outlets.

In 2019, 10.2 per cent of editors-in-chief in regional newspapers were female. In nationwide newspapers, 20 per cent of editors-in-chief were female (Pro Quote Medien, 2019: 23). The liberal-left newspaper taz has the highest number of high-ranking women (50.8%), followed by the weekly Die Zeit (33.7%) (Pro Quote Medien, 2019: 24). The ranking in Figure 2 reflects the whole print sector.

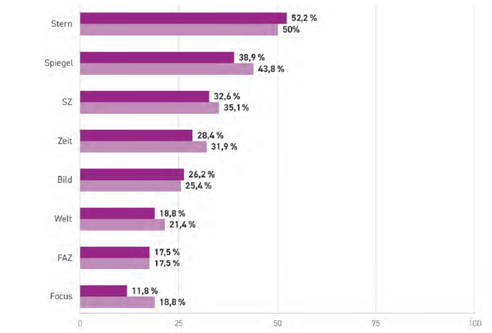

The top (darker) bar indicates the “women’s power index”, consisting of high positions in the hierarchy, whereas the bottom (lighter) bar shows all leading positions, including middle and lower management.

(Source: Pro Quote 2019, p.52).

The print magazine Stern has the highest “women’s power index”, with 52.2 per cent women at the highest level of the hierarchy; the news magazine Focus has the lowest, with 11.8 per cent and a 7 per cent gap between that and the scale which also features middle and lower management. In the online editions of traditional newspapers, the number of women in leadership is higher.

The editors-in-chief of the popular magazine Stern and the news magazine Der Spiegel pointed out in interviews that no internal rules, recommendations, codes, or guidelines to support and promote women journalists in their careers are in place. One chief editor is concerned about the cultural aspect of homogeneity within editorial units and its potential influence news stories:

For me, it is this aspect that I would call unconscious bias […] because what worries me is what we do not see. And democracy is also the participation of the many and […] we [journalists and editorial units] naturally live in our own bubble. […] the media companies [in Germany] will not be able to hire on a large scale in the next few years. The possibility of change through people we bring in from outside is very limited […]. But how do we ensure when generating our topics […] that we are not blind?

However, at Stern, a top-down order finally enforced gender parity amongst their staff. This parity has not yet been reached in the gender pay gap. One editor-in-chief of a major paper says, “According to my […] – and I have to know – it is not the case that women are paid less than men. In my observation, women earn as much (or little) as men”.

At the second-biggest newspaper, Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ), women can take advantage of a variety of support schemes, like coaching or lunch talks with members of the executive board. There is basically no difference between women’s and men’s salaries, and staff is paid the standard wages according to their position. The weekly Die Zeit helps women combine professional and family life, as there is no mandatory attendance in the company, and meetings take place at family-friendly hours. Moreover, Die Zeit’s staff is especially aware of gender-sensitive language. However, looking at the bigger picture, gender equality in the German media landscape is still based on opaque and localised measures.

I have a watchlist […] with women in investigative journalism […], which is an imaginary pool of female colleagues, where I see whether they would be something for us at a certain point. […] But it is not […] that we have an automatic process for measuring and advancing gender equality in media.

The broadcasting sector shows slightly different patterns, whereas in public service media, the staff sometimes consists of one-half to two-thirds women, but they only make up 30–50 per cent of leading positions (Pro Quote Medien, 2018: 51). In commercial broadcasting, women also face this glass ceiling with an average of around 20–30 per cent reaching leading positions (Pro Quote Medien, 2018: 60–65).

Interviewees in the public service television sector reported that special awareness and some child-care assistance are the only instruments that currently exist to support female journalists. Although the figures differ from what the interviewee of the commercial sector said, the respondent from RTL said that diversity is of high importance. The broadcasting station established a special unit to empower female talent and professionals to take up leading positions. At least in middle management, women journalists outnumbered men. Again, there is no systematic tool, like a quota, but a special sensitivity to support women, such as with family-friendly working hours: “[We’re trying] to get women into these leadership positions – why? Because our news and magazines are mostly watched by women”.

Only one respondent in the sample of the leading news media made clear that there is an informal rule to positively discriminate against women and support their careers. A quota system as a formal rule is not in place in the leading news media. However, the female journalists’ association Pro Quote monitors media’s commitment to gender equality and publishes reports and easy-to-grasp graphics about the state of women’s careers in news media and hence functions as a pressure group. National legal frameworks enforce gender equality at the workplace with opportunities for parental leave.