Gender equality and women’s rights in the workplace have been often overlooked issues in South Korea. Gender inequality and glass ceilings are not unique to the media industry, and the 2018 Global Gender Gap Report from the World Economic Forum (WEF) ranked South Korea 115th out of 149 countries in gender equality (World Economic Forum, 2018). Out of the four factors measured by the WEF index, economic participation and political empowerment stand out as areas of weakness in comparison with educational attainment and health and survival. Placed 92nd for political empowerment and 124th for economic participation and opportunity, South Korea has fewer female lawmakers or high-level public officials and a wider wage gap than other countries, which is also reflected in the media industry. Such a social milieu is closely linked to the opportunity windows for female reporters to be assigned to major positions, which is inevitably linked to career advancement. This becomes not a matter of competence, but an issue of lacking social networks crucial for sourcing stories.

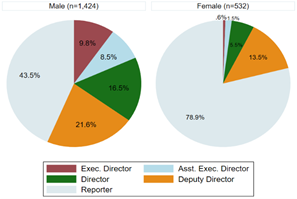

According to the 2017 Korea press yearbook[KC1] , 71.6 per cent of the journalists in the news industry were male (21,940) and 28.4 per cent were female (8,707) in 2016 (Korea Press Foundation, 2017). Since then, female journalists have grown in number, reaching 31.5 per cent (9,872) in 2018, but the gender gap persists. Gender gaps are even more evident in high-ranking positions. 78.9 per cent of female respondents and 43.5 per cent of male respondents are rank-and-file reporters, and 92.5 per cent of female respondents hold positions that are deputy-level or below. This far exceeds the 65.2 per cent of the male respondents who hold positions at or below deputy level. However, the ratio reverses in higher rank positions: 34.8 per cent of male respondents hold positions above the director level, while only 7.5 per cent of the female respondents do (see Figure 2).

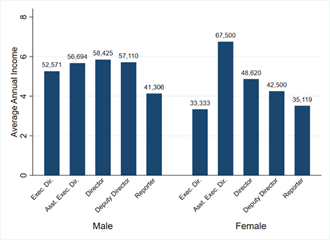

Although published almost a decade ago, the Global Report on the Status of Women in the News Media (International Women’s Media Foundation, 2011) offers insights into South Korean women’s work environment in the media industry that are still very much relevant today. South Korean women are, as in many other areas, pursuing journalism more actively than before, and the report depicts an increasingly open work environment for women. The study reports fairly equal full-time employment with benefits for both sexes, where there is little to no gender difference in lower-range salaries. Many news media have more female reporters at the entry-level. In 2018, the salary gap is as present as ever, with some exceptions in rare cases where women hold high-rank positions (see Figure 3). Theglobal report’s findings are also consistent with the more current Korean Journalists Survey 2019, in that more men hold higher-rank positions than women (see Table 1). In 2018, there are still virtually no women in top-level management, suggesting that women have little say in what gets reported and on what terms (Korea Press Foundation, 2018).

[supsystic-tables id=79]

According to the 2018 article from the Journalist Association of Korea, some print newspapers do not have any female directors in their newsrooms, despite a substantial number of female journalists (Kim, 2018). Among the major newspapers, Kyunghyang and Hankyoreh have the highest overall ratio of female reporters. Out of the 259 journalists working for Kyunghyang, 85 (32.8%) are women, and 5 out of 25 deputy director-level positions and above are held by women. 93 out of Hankyoreh’s 275 reporters are women, which makes up more than a third of their entire workforce. 14 out of 60 executive officials above the deputy director–level positions are women. JoongAng Ilbo is the only national daily with a female editor-in-chief.

While there is much room for improvement in gender equality and representation in the newspaper industry, the broadcasting industry has even thicker glass ceilings that have kept women from reaching the executive director positions in all of the three major terrestrial broadcasters. KBS has only two female directors, a mere 9.5 per cent of the 21 management-level employees, which means that fewer women get to participate in the decision-making process in news production meetings. MBC and SBS are not very different in their gender makeup, despite a slight increase in the number of women in deputy director- and director-level positions in recent years.

The marital status of respondents from the Korean Journalists Survey 2019 is also reflective of the working environment of women in the news industry (Korea Press Foundation, 2019c). In 2018, 71.3 per cent of male journalists were married, but only 31.4 per cent of the female journalists were, and the number of female journalists drops even further (21.2%) when asked if they have children (Korea Press Foundation, 2018). Such a pattern can be explained by the social pressure put on women to leave their job for marriage and family. The difference in the average age of male (42.6 years) and female (33.4 years) respondents is reflective of women’s relatively recent entry into economic participation.

The Child Care Act (Article 14) dictates that any business with at least 300 full-time female workers or at least 500 full-time workers establish, joint-operate, or contract a workplace childcare centre. Given that approximately 400 to 500 employees work part- or full-time for each of the major national dailies, childcare is not always guaranteed. Larger broadcasters like the major terrestrial broadcasters do provide childcare to meet this mandatory requirement.

The nationwide #metoo movement in 2018 sparked changes in the news media, giving rise to specialised departments like a gender equality centre, committee for gender equality, and gender desk in media companies to promote gender sensitivity and identify and resolve gender-related issues internally. KBS first adopted gender equality rules in 2019, expanding its previous guidelines for sexual harassment at the workplace to include measures for equal treatment of both sexes as well as disciplinary measures for sexual misconduct. SBS and MBC, along with other major news media, revised their disciplinary code for sexual harassment and assault to better accommodate victims and impose stricter discipline on their perpetrators. These efforts, albeit overdue, are expected to foster gender-sensitive work environments and systematically improve women’s working conditions, while also changing stereotypical and discriminatory coverage of women in media.

In the news industry, the Korea Woman Journalists Association has advocated for the rights of women in the media industry and promoted gender equality since 1978 through research, training, publication, networking, and study-abroad opportunities for female journalists. Organisations like the Korea Women’s Associations United and other government agencies dedicated to promoting women’s rights also offer commentaries and research on gender equality in news coverage and media content.